cw: childhood trauma, domestic abuse, alcoholism, drug use

The more I write, the more I think of things to write. The more I think about what I want to write, the more ideas that drip into my head like percolating coffee.

I’ve been listening to a lot of music — which is extremely normal for me (I have at least several dozen Spotify playlists) — but Heartbreak Dreamer by Mat Kearney has in particular been giving me goosebumps today.

This is for the hard men who want love but know that it won’t come

from ‘Heartbreak Dreamer’ by Mat Kearney

For the ones amendments do not stand up for

For the ones who are forgotten

For the ones who are told to speak only when you are spoken to

And then they are never spoken to speak

Every time you stand you do not forget yourself

Do not let one moment go by that doesn’t remind you

That your heart beats a hundred thousand times a day

And that you have gallons of blood making every one of you oceans

I listened to the Inside album (the one by Bo Burnham) on repeat while I was making soup for dinner last night. The collision of feelings and lyrics from multiple songs has me a little bit understood, a little bit jumbled up, a little bit lonely, a little bit connected to everyone — especially people I don’t actually know (yet). It feels like an experience that is somehow a blueprint of my life written in hooks and rhythm.

I grew up in what I generally describe as a fundamentalist evangelical home. We were homeschooled, opening giant boxes smelling of books every autumn. Mom taught us until we could mostly do it ourselves, and then she just … stopped. Every week, we attended a tiny church forty stifling minutes away by car. Sundays were Dad’s weekly opportunity to lecture us about all the things we had done wrong, forty minutes back from church. After my mom left him and asked for help from the church leadership, they disbelieved her in that specific way that white cis religious heteronormative patriarchal men tend to do when you ask them, sobbing, for help because your husband is screaming at everyone and threatening your kids and he killed a man over drugs after getting out of the Army back in the 70’s and there are rifles and shotguns on a gun rack, polished and ready and within arm’s reach, right there next to you in that room. I suppose they didn’t believe her because they didn’t want it to be true, or they didn’t believe her because that was never their experience of him; either way, it was a shock to her that they didn’t care.

Years later, my dad checked himself into a rehab facility to get treatment of his addiction to pain pills. I didn’t know anyone else that had done that, and I was honestly proud of him. This was back when I had a little hope, every now and then, that I could have a relationship with him that wasn’t built on fear and disapproval and anger. I went to an informal meeting there on the day that I visited him, specifically for the families of the people that were checked in there.

About a third of the way through the slides with bullet points about the ways families tend to protect themselves when an authority figure is a rollercoaster ride of rules-I-just-made-up and anger that seemed to come from nowhere, sandwiched between hugs and professions of love, it dawned on me that he’d always been addicted to something. I could see the patterns of abuse and destruction and performative love and abuse and destruction and performative love, and I can never unsee it. My entire childhood was recontextualized, and even though I’ve since separated myself from both parents, I am grateful for that flash of insight and that it happened because he was performing recovery.

It might sound spiteful of me to call his recovery performative, but he only ever sees the world through his own eyes, never anyone else’s. That recovery wasn’t real; he replaced Vicodin with pot and scotch and probably other things I don’t know about. Nobody else’s feelings or opinions matter to him. Nobody else’s comfort or discomfort will ever change his mind. Nobody else’s life experience will occur to him. It can’t, because he can’t, and it’s okay that I stopped trying to have a one-sided relationship. Once, my mom told us a secret that she’d kept for decades: that he kept his empty beer cans in their bedroom closet for the entirety of our childhoods, and as soon as she said it, I knew our growing-up years weren’t *like* we were living with an alcoholic; they WERE us living with an alcoholic.

Nearly all my stories from childhood are horrifying to anyone that hears them. I tell them so that I can better understand my experience, or maybe to let the pressure out that built up when I was single digits old. There are entire blocks of years that I don’t even remember, like black holes that bend matter around them.

“For the ones who are told to speak only when you are spoken to

And then they are never spoken to speak

Every time you stand you do not forget yourself.”

Mat Kearney

I shook the dust from my feet and some days I have to do it over again, but I don’t regret doing it and I don’t regret who I am or what shaped me.

The more parenting I do, the more I realize that we give our children reasons to go to therapy even when we are doing our best. They’re people too. We can’t decide for them how to understand us, or our decisions, or our pain. I think one of the only things I can teach my kids is how to shake the dust from their feet when leaving is what’s best. That, and how to communicate and what consent means. But especially, that sometimes leaving is exactly the right thing to do, and to trust and listen to yourself. You’ll know.

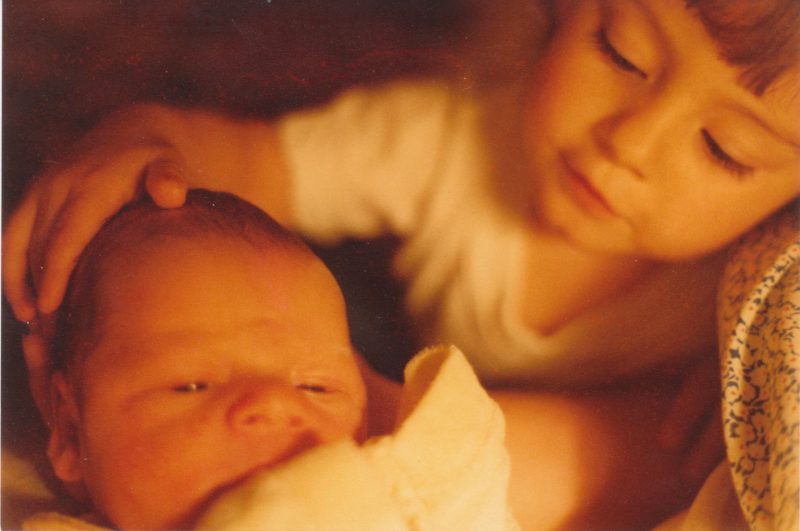

featured image is an old photo of my baby brother and me not long after he was born, taken by my dad